Chapter notes

Photo: Clem Albers, “Military Police on duty in watch-tower at Santa Anita Park assembly center. Arcadia, California,” April 6, 1942. National Archives, Washington D.C.

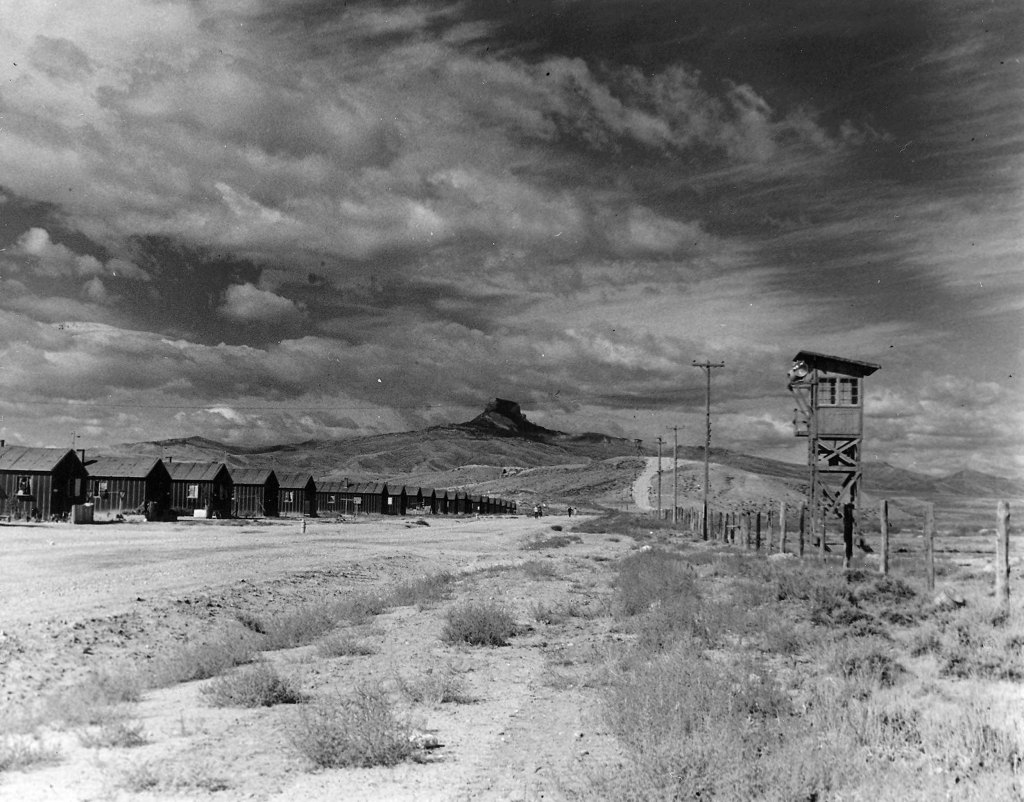

Photo: Yoshio Okumoto collection, courtesy Heart Mountain Wyoming Foundation) “Avenue I. Guard tower at North end of Third Street. See guard tower on hill at end of road in deep background. Picture take late in camp’s life as guard towers are not manned. Blocks 28 and 29 on left.”

Photo: George Hirahara, “Group portrait of military police by railroad tracks,” June 15, 1944, George and Frank C. Hirahara Photographs (sc14b01f0101n01), Manuscripts, Archives, and Special Collections (MASC), Washington State University Libraries.

SECURITY

The security measures employed at the three assembly centers that sent their prisoners to Heart Mountain – two in California (Pomona, Santa Anita) and one in Oregon (Portland) – employed robust rings of redundant security measures to ensure these Japanese people could not engage in espionage, sabotage, or terrorist activities aimed at the many military and industrial war-related facilities throughout California, Washington, and Oregon. Each assembly center was ringed with barbed wire obstacles of such complexity and strength that they could only be breached using military explosives. Guard towers contained powerful floodlights, and soldiers whose orders were to ensure no prisoners escaped were armed with automatic weapons. Censorship of incoming and outgoing mail, periodic inspections of everyone’s possessions searching for weapons, radios, explosives, even family photographs, books, letters, papers written in Japanese, and seemingly innocuous items such as scissors, kids baseball bats, and mirrors (which could be used for signaling).

While companies of military soldiers secured the perimeter of each assembly center from the outside, another security force on the inside, composed of Caucasian civilians (aka policemen), performed inspections, censorship, and ensured curfews were not violated. Inspections were conducted multiple times, day and night, by this internal police force, and they were authorized to enter and search anyone’s living space at any time for any reason.

The relocation centers built inland in the Western states, including Heart Mountain, were in remote areas far removed from large population centers, critical infrastructure facilities, or war-related structures. The security features at the Heart Mountain Relocation Center differed considerably from those found at the assembly centers. Security characteristics appeared less severe, almost amounting to token forces. For example, beginning in the Spring of 1943, the nine guard towers surrounding Heart Mountain were unmanned, remaining unmanned throughout the remainder of the Camp’s life. The fence around the Camp consisted of wooden posts five feet high supporting four strands of barbed wire, the same type of fence found throughout Wyoming to control range cattle. This fence could be ‘beached’ easily as young boys in the Camp did regularly. Military police soldiers assigned to guard Heart Mountain were not issued automatic weapons (machine guns). Day and night motorized patrols, ordered by the military, were never performed, nor was mail censorship; inspections of people’s possessions did not occur, nor did searches of people’s apartments. The internal police force at Heart Mountain consisted of Japanese residents sworn to uphold Wyoming laws and apprehend those who violated them (as opposed to treating residents as ‘foreign secret agents’). A large part of their time was spent writing speeding tickets to drivers of government vehicles supporting the Camp’s population.

This dichotomy appears to have occurred due to intense and deep-seated racism occurring in the federal government, California state government, and social, civic, and industrial entities throughout California. They wanted these unwanted Japanese removed from California immediately and did not want them back. The severe security measures around assembly centers may have been built to please these powerful political forces and were highly visible to the press and to the general public.

In contrast, the relocation centers located throughout the Mountain West in out-of-the-way places, virtually inaccessible to the press in wartime America, didn’t need to satisfy this racially driven political pressure. Simpler and cheaper security features could be built. Indeed, the true security entity keeping the Camp’s residents from escaping was the scarcely-populated, wild, unforgiving rural terrain of northern Wyoming.