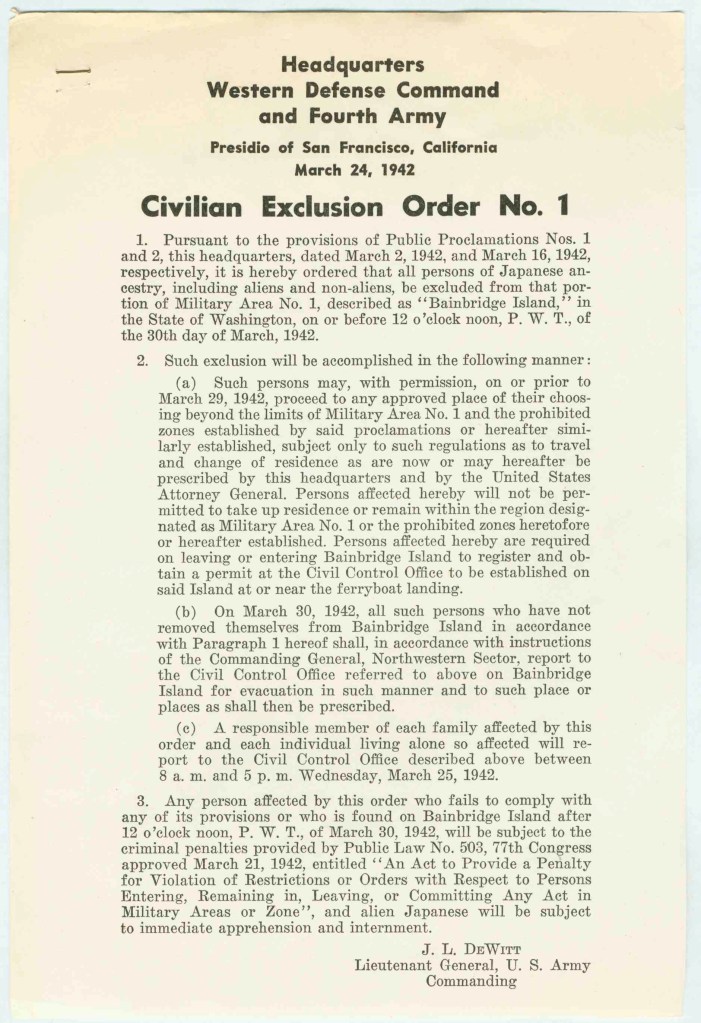

Exclusion Order No. 1, dated March 24, 1942, affecting evacuees on Bainbridge, Island, WA. They were given until 12:00 o’clock noon, P.W.T. (Pacific War Time), March 30, 1942 (six days) to prepare for evacuation. Courtesy of Japanese American Veterans Association.

Los Angeles evacuees being evacuated to the Santa Anita assembly center. Photo: Gordon Wallace, “Buses line the street at 23rd and Vermont,”March 1942. Los Angeles Times, May 1, 1942.

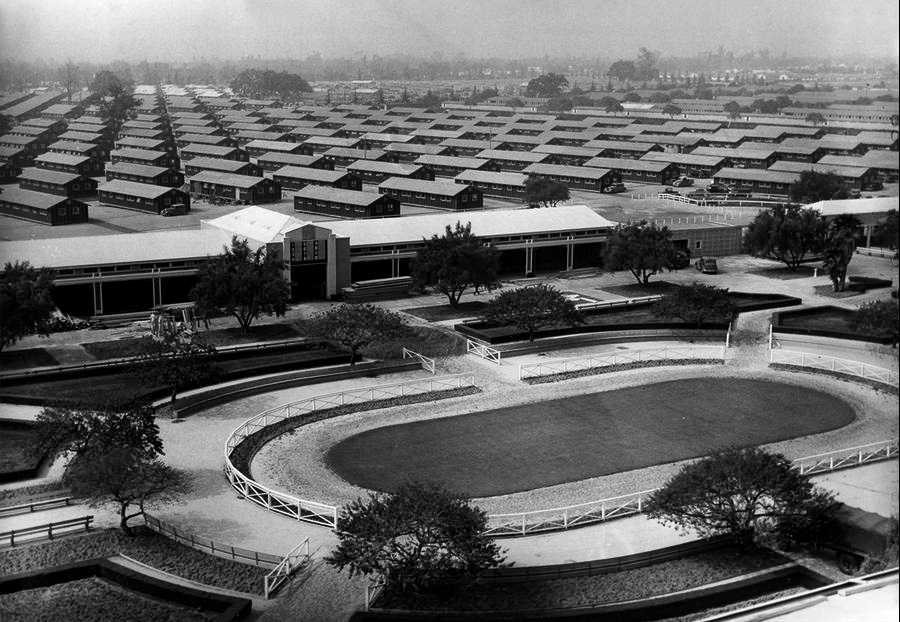

Photo: Clem Albers, “Santa Anita Assembly. Arcadia, California. A panoramic view of the Santa Anita Assembly center showing barrack apartments on the former race track grounds for evacuees of Japanese ancestry. They will later be transferred to a War Relocation Authority center to spend the duration. April 6, 1942. National Archives, Washington D.C.

THE DECISION TO EVACUATE

Pearl Harbor came as an existential shock to America even though the government had, for years, anticipated such an attack from Japan. Longstanding racism targeting oriental persons living in California, Washington and Oregon immediately used the attack on Pearl Harbor as an excuse to accomplish a goal long sought by economic, societal, and governmental (both state and federal) interests – rid the West Coast of all persons of Japanese heritage, both alien and native-born.

The intense political pressure arising from the attack, targeted the federal government and the government of California fueling a legal, social, political, and deeply personal dialog between the Department of Justice (DOJ) and the War Department [1] over what to do with 115,000 persons of Japanese ancestry all of whom were considered to be loyal to Japan. The War Department sought to remove all Japanese from the West Coast and put them in prison camps to be built inland in the Western state as soon as possible. The DOJ resisted this attempt, considering it unconstitutional. Throughout this dialog, the Japanese had no legal representation. Politically, they were powerless.

The Army, represented by the Western Defense Command/ Fourth Army and commanded by Major General John Lecesne DeWitt, was one target of this intense racially-inspired political pressure. General DeWitt was responsible for defending the entire West Coast of America and Alaska from an impending attack on the mainland from the victorious Japanese navy who were, falsely, reported to be approaching the coast. He saw himself surrounded by enemies: he imagined the Japanese fleet approaching and over 100,000 saboteurs of Japanese ancestry in his backyard waiting for a signal from Tokyo to rise up as one and strike a fatal blow to the ports, airfields and aircraft assembly plants scattered all over his command. DeWitt was a racist — this characteristic ultimately cost him his command. He was easily swayed by the numerous entities in California howling for the removal of the Japanese from the Coast. The pressure caused DeWitt to make decisions based on racist fear instead of military facts. His near panic moved up the chain of command ultimately causing his military superiors and their civilian bosses to recommend to President Roosevelt to incarceration of the Japanese.

On February 19, 1942, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066. Evacuation and incarceration began.

When war came to America, Major (later Colonel) Karl R. Bendetsen was assigned to the staff of Major General Allen W. Gullion, the Army’s ‘top cop’, whose title was Provost Marshall General of the Army. Bendetsen was a key decision-maker on what to do with these Japanese people. Still, he was the only one of the many decision-makers who played a significant role in carrying out the evacuation decision that was ultimately made. After the President signed EO 9066 on February 19, 1942, Colonel Bendetsen was assigned to the staff of Major General John DeWitt, commanding the Western Defense Command/Fourth Army, and was assigned the task of implementing the executive order – rid the West Coast states of all persons of Japanese ancestry. Bendetsen was given terse guidance by DeWitt; to move them out at maximum speed and minimum cost.

Acting swiftly as directed, Bendetsen conceived a two-step evacuation process. First, at maximum speed, build assembly centers near Japanese population centers where people could be removed from their homes and held in heavily guarded camps as quickly as possible. To this end, fifteen centers were built, most of them in California, in and around preexisting facilities such as fairgrounds, racetracks, or similar sites where utilities already existed. All fifteen centers were constructed at the same time — in less than a month. The existence of these assembly centers and the swift occupation of them was highly visible and politically popular.

With these would-be saboteurs locked up, the second step of Colonel Bendetsen’s program began; building more permanent prison camps away from the Coast placing them in inland western states in remote areas where their imprisonment would continue. Ultimately ten ‘relocation centers’ were built. The Heart Mountain Relocation Center was one of these. Construction began on June 6, 1942, and ended with the arrival of the first of 11,000 persons occurring on August 12, 1942.

[1] Now called the Department of Defense.