Chapter notes

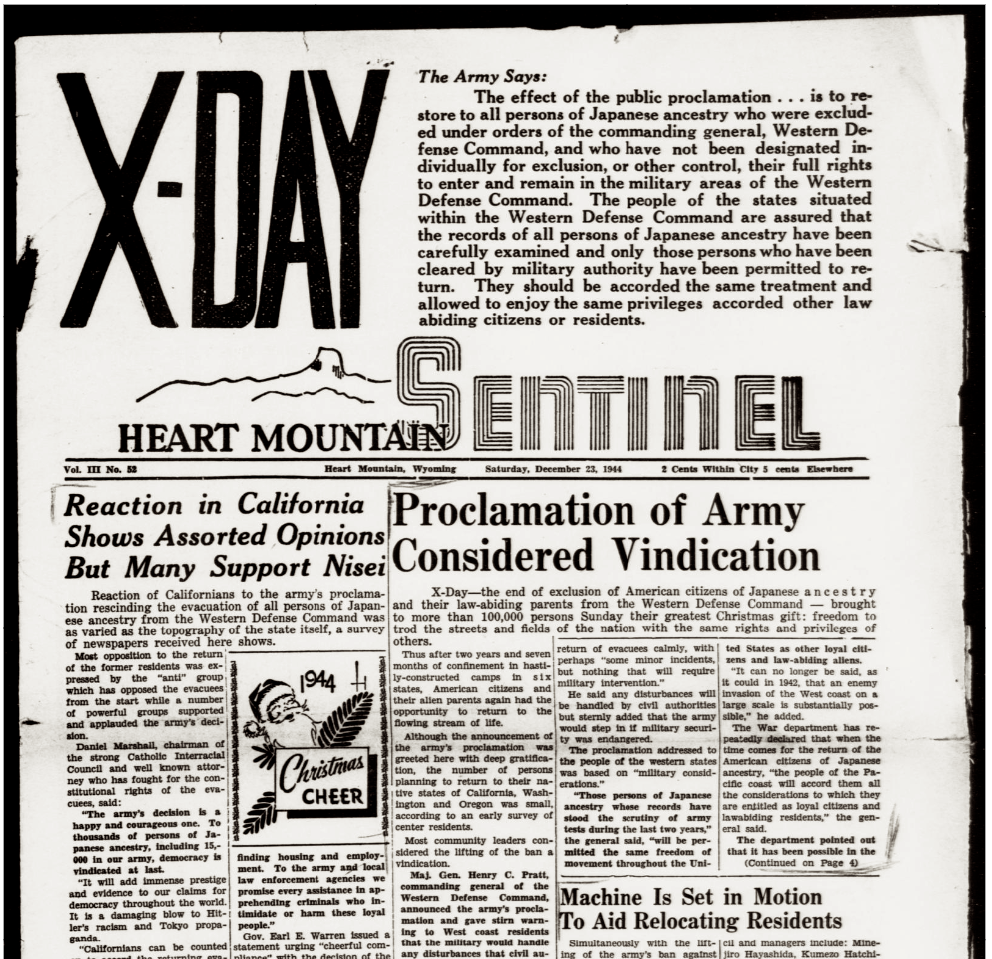

“Proclamation of Army Considered Vindication,” Heart Mountain Sentinel, Vol. III, No. 52, December 23, 1944.

Special Train No. 4 and the crowd of residents who assembled to say good-by to friends and neighbors leaving for their old homes in California or for new ones in the East. July 6, 1945. Photo: Yone Kudo, “Departure from Heart Mountain concentration camp, Wyoming, July 1945.” National Archives, Washington D.C.

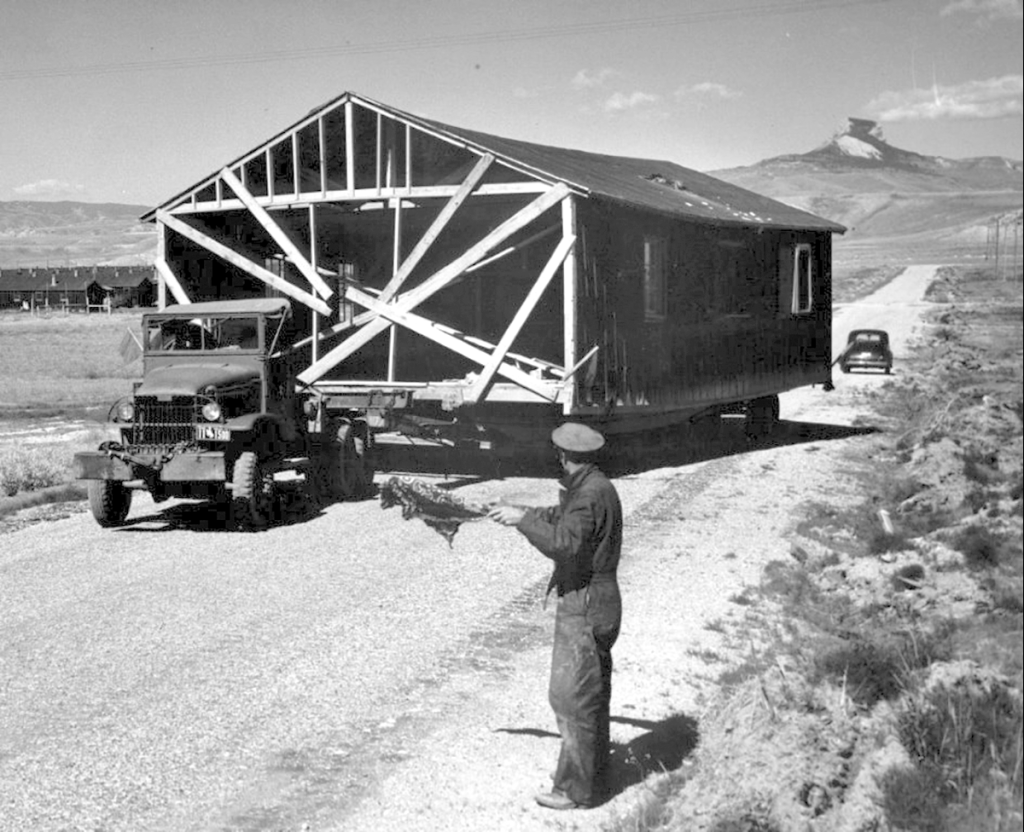

Henry McIntosh moving half a barracks building to a homestead. Note remaining buildings in left background. Photo: Courtesy of Ashley Scott, Cody, Wyoming

Photograph of the Camp in late 1949, four years after the Japanese-Americans left. Photo: B.D. Murphy.

Historian Roger Daniels put it succinctly:

“Putting the Japanese Americans into camps took only a few months but getting them all out again took almost four years.“

And, for many residents, leaving the Camp proved to be as traumatic as it was entering the Camp, three years and three months prior.

The December 23, 1944, edition of the Sentinel in three articles, all on page one, revealed a broadside of information that seemed to be more troubling than joyful for many of the Camp’s residents. First, in two-inch high font it was announced that on December 14, 1944, General Henry C. Pratt, commanding general of the Western Defense Command, signed Public Proclamation number 21, rescinding all 108 exclusion orders, the curfew and evacuation orders imposed on people of Japanese ancestry living along the West Coast by General John DeWitt, General Pratt’s predecessor, during the Spring and Summer of 1942. They could go home again!

Second, the X-Day edition announced the Supreme Court’s decision on the Ex Parte Endo vs United States case. The Court held that the War Relocation Authority had no statutory authority to detain Endo or any other person of Japanese ancestry if their loyalty had been certified. They were free to leave the Camp whenever they wanted (at least in theory)!

Finally, all the relocation centers, except Tule Lake, would gradually close, the final closing date to be no later than January 2, 1946. The residents, seemingly were being kicked out!

Each resident leaving the Camps would receive a transportation voucher, a relocation grant of $25 and a subsistence grant of $3.00. Appropriations to compensate the Japanese for their enormous losses caused by the evacuation and imprisonment, or appropriations for assisting them to re-establish themselves when the centers closed, apparently wasn’t a humanitarian obligation or a political necessity.

Between May 16, 1945, and November 9, 1945, twenty special trains left Heart Mountain, ultimately turning the Camp’s residential area into a ghost town.

In November 1945, a fixed asset inventory of the entire Heart Mountain Relocation Center was conducted by the Bureau of Land Management (part of the Department of the Interior). It was completed on December 1. Subsequently the Camps’ entire infrastructure came under the administrative management of the Bureau.

With a complete town (once the third largest in the state) and all of its assets and resources coming under its control, the Bureau was anxious to begin unfinished work; it had a lot to do.

- Prepare the irrigable land for homesteading, including making the barracks buildings available to returning servicemen for use as temporary living quarters or for any other homestead purpose. This task was the Bureau’s primary responsibility for which buildings and equipment within the Camp were to be used.

- Restart construction work on the Shoshone Reclamation Project, halted when the war started. This was the Bureau’s second most important task. Any buildings and equipment not needed to support homesteading was used in the construction work.The Bureau eventually moved the headquarters of the Shoshone Reclamation Project from Powell and housed it in the Camp’s many vacant buildings, saving lease and rent expenses.

- Secure the residential area; drain wash house and mess hall boilers, turn off electricity and the water, remove the thousands of coal stoves, provide fire protection and physical security. All blocks in the residential area were secured except for block 23, which was maintained as single room apartments for use by Bureau employees, contractor personnel and temporary housing for homesteaders.

When the authors’ family lived at the Camp from 1948 to 1950, several hundred people made their home in the administration area. The Bureau of Reclamation’s Missouri River Basin Project Design Unit and the Shoshone Reclamation Project headquarters were both located at the Camp. Block 23 apartments had an average occupancy rate of about 60-70 per cent most of the time. In addition, contractor personnel may have lived onsite. The overall population of the Camp was perhaps 300 to 400 residents.

Thus, closed the first part of the Heart Mountain Relocation Center’s unusual life. The Japanese lived there for about three years and three months; the Bureau maintained a diminishing presence at the Camp until early 1953, a period of eight more years. These were eventful years, as the Shoshone project neared completion and the land, now with access to irrigation water, was opened to homesteading.

The ten relocation camps forever and indelibly changed the lives of the people who were forced to live in these marginal facilities; America was forever changed too. The people of Japanese ancestry left the camps behind taking with them honor, patriotism, perseverance, courage, and faith in their country—a faith sorely tried by the treatment they endured. America left the camps behind too, but her mantle stained by racism, beginning at the top with the President. The leaders in every level and branch of government failed these citizens to the point it seemed that the hand of every man was against them. They endured evacuation, incarceration and resettlement with obedience, patience, and dignity. What else could they do?

Shikata ga nai.